“Everything is only for a day, both that which remembers and that which is remembered.” (pg. 682, East of Eden)

When I moved away from home, I had no idea what was in store for me. I didn’t know how I would fit in— I didn’t even know where I would live. It was a near blind leap to Toronto, one that took me through the loneliness of my first winter to smiling across the table at my best friend to waking up at four a.m. for opening shifts to seeing my favourite musical on the stage.

That blind leap had turned out so well, and I knew exactly how fortunate I was: studying and working in a city driven by money makes the life you build feel tenuous and dependant on the direction of the wind.

But it came time to move again. Fortunately, or unfortunately, life doesn’t stand still. Time moved forward, and my work contract moved closer to its end date and I hadn’t been able to get back to university in Toronto, so something had to give.

This time, the move to Hungary was less of a blind leap. I knew things would always feel at least a little different from home; I knew immigration processes were a special kind of purgatory; and I knew that loneliness can become a physical ache. And that clarity made this move challenging in different ways.

However, in this photo essay I just want to speak about remembering. I keep recalling fond memories and feeling empty spaces, and the Vuyo in those recollections feels nearly different from me. I do not have all their books; I am not laughing with their friends; I am not sitting in their room. How changed am I for not having their surroundings?

Everything

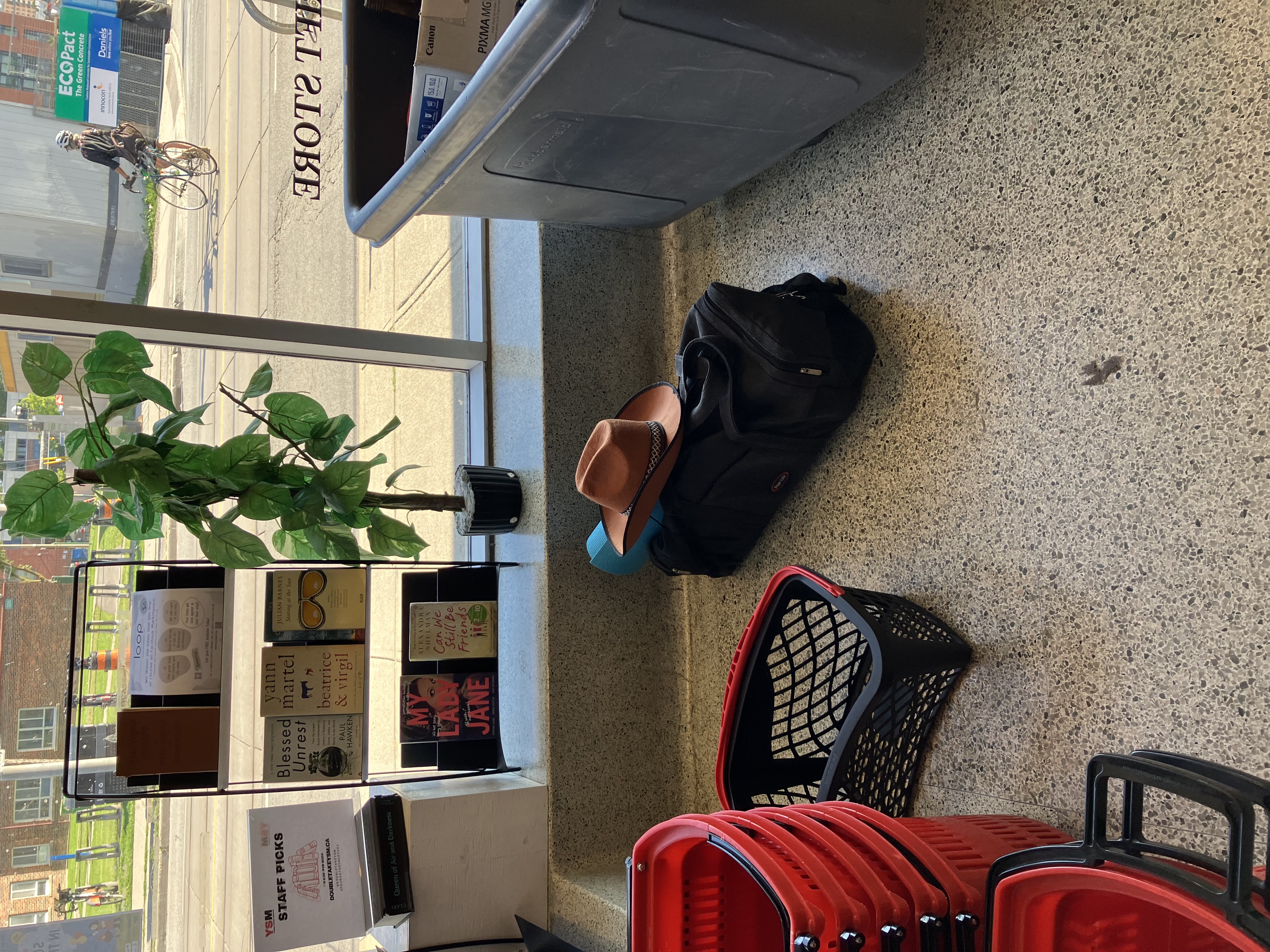

I could not fit two years of life into four suitcases. My last few hours in Toronto were spent excising things from my life: unworn clothes were walked to the charity shop, linen left for the next tenant, and books slotted into Little Libraries.

I could not take Saturdays seated at a table, powering through chips and cherries, with the sound of disappointed groans after the wood-resin tap-tap-tap of a rolled die. I could not fit late afternoon bike rides home, riding in the shade of skyscrapers. I could not fit walking downstairs and having a space made for me at a dinner party.

When I moved to Canada, every time I saw a person who looked like someone I knew back home, it plainly shocked me. Earlier this week, in the halls of my dormitory in a small town in Hungary, I walked past a couple of people who looked like colleagues, and was surprised at the sting of quickly dashed and irrational hope.

I find myself dizzy with wonder in this new place, with nothing familiar to lean on. I find myself sad around strangers, with nothing familiar to lean on. All the surfaces I had grown accustomed using to re-orientate me on confusing days are gone, and with it my easy comfort. It’s like walking around a new house in the wee hours of the morning: I keep stubbing my toe on jutting corners, but I’ve never seen the starting rays of the day from this window.

Which is Remembered

Between South Africa, Canada, and Hungary, I’ve seen three standardised ways to make windows, toilets and public garbage bins. It’s these small mundanities that fascinate me— they, perhaps, tell me the most that things are different. Things are different because the people have needed the same thing and come to different conclusions. It’s informed by cultural preference and consensus, land regulations, and timing. There are so many stories out there about alternate universes, and each country feels like that: one thing was different and they hurtled in a different direction.

The streets of my small town look so much like Cape Town, but the language spoken re-contextualises it all. The towering trees and the crawling leaves smell like Cabbagetown, until I turn the corner. There are so many imperfect replicas, the differences charming or saddening— depending on if I’ve eaten lunch yet.

A Day

The following prose borrows some language and terms from mathematics, because the more I study it, the more its rhythms and reasons shape how things feel and how I remember them.

When I recall the past four years and how much has changed, at times it I understand it discretely and at others, continuously.

For the purposes here, discrete means each thing — each element — feels distinguishable and I could count all of them, if I had the time.

It feels as I went from sharing a tent with my best friend to being trapped in the house for unending months to seeing my first snow to watching an absurd French film to writing in my dorm at dawn. Each of them can warrant a smile or specifically inform a later decision.

However, yes, they all began and they all ended, but I omit the precarious drive up the cliff to the campsite, the relief of sitting in parks after quarantine, that first excitement at thawing spring and a precarious walk down a hill from class. That is where the term continuously is helpful: there is no sudden jump, only the gradual walking of the path, however steep or plateauing it feels.

All this is to say that this ending, this moving, for a moment, felt like the snipping of a thread. Now, with the gift of retrospect and my great-aunt being laid to rest, I think it was the headlong rush that is going from 222 to 223.

The path I am walking is long — it started being drawn long before I was born, and I am just fortunate that it’s my turn now. I will just have to be happy with dragging my finger across the course carved to remember what it felt like,

and keep collecting new moments for it.